In Gratitude: Thank you Deborah and David for giving us permission to reprint portions of your book edifying our students and teachers who participated in the Iona Project. Your words brought into contact with the prayers of the past making them real for the present and future!

INTRODUCTION

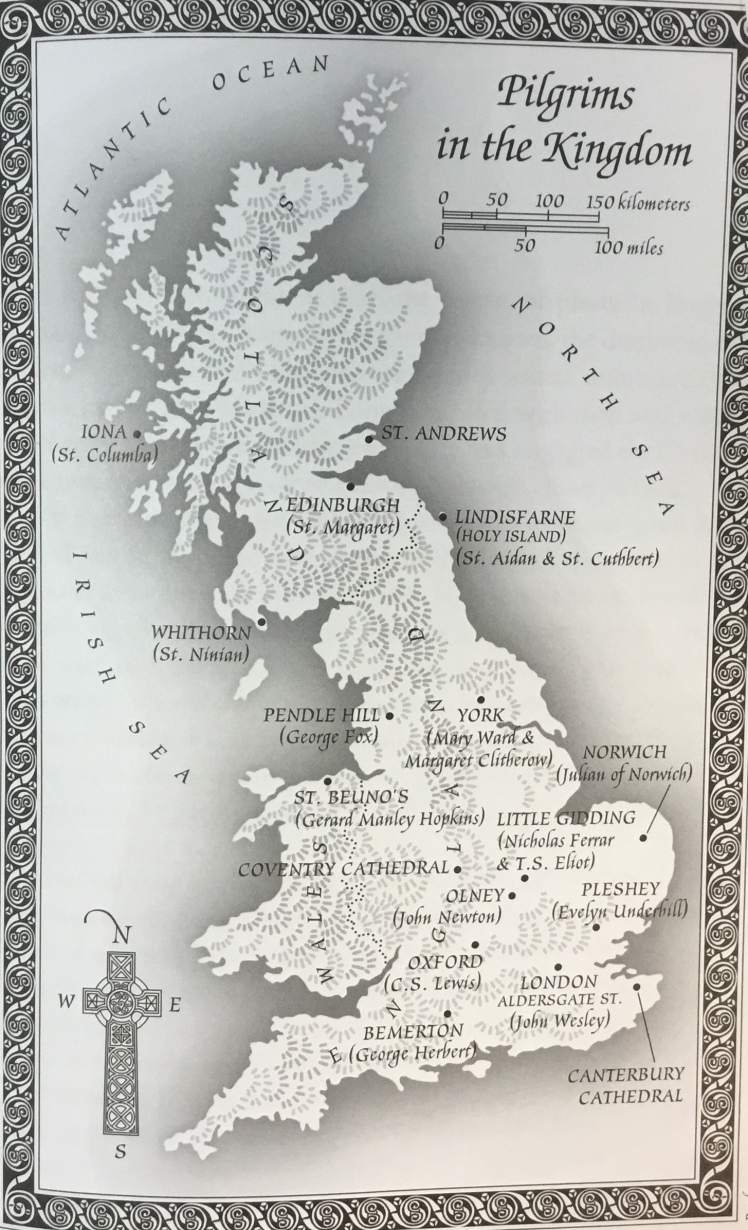

The journey began for us with the names of places in England, Scotland and Wales. Some sites were well-known, the destinations of ancient pilgrimage trails. Others were seldom visited, unmarked on all but the most tenacious maps. Long identified with men and women who had lived their faith boldly, each place had mediated the Christian story over the centuries, often drawing travelers closer to God.

With the prospect of a sabbatical year away from our work in the United States, we pored over a map of the United Kingdom, pencils in hand, as a tentative itinerary came into view. Britain provided a breadth of Christian landscape perhaps unsurpassed in the world, with sites steeped in Celtic, Catholic and Protestant traditions. Beckoning us were chapels and sea caves, mountains and cathedrals, retreat centers and holy islands. Could sojourning in these places, listening more attentively to the lives of people linked to these sites, help us understand their experiences of God and, more to the point, bring us closer to God as well?

We had long known of Iona, for example, off the west coast of Scotland, where Saint Columba founded a monastery that illumined much of northern Britain. But what would it be like to walk the island? How did you get to it, and where would you stay? Why does the Celtic saint’s legacy attract people even today? “To tell the story of Iona,” one writer noted invitingly, “is to go back to God and to end in God.”

Methodist friends had often alluded to John Wesley’s Aldersgate Street experience. In some ways Methodism traces its history to this corner of London where Wesley had felt his heart “strangely warmed,” overwhelmed with an assurance that his sins were forgiven. Could we return to Aldersgate, not to recreate Wesley’s experience- as though epiphanies could be snatched like butterflies–but rather to glimpse his understanding of God’s forgiveness, that it might shed light on our own?

The ancient city of Norwich harbored a memory of Lady Julian, the fourteenth-century mystic who wrote zealously of God’s love and provided spiritual advice from her solitary cell. By immersing ourselves in Julian’s writings and prayerfully returning to sites associated with her, could we ourselves sense more fully God’s imperishable love?

Britain offered this spectrum of Christian sites from the fourth century to the twenty-first all within a nation smaller in size than our home state of New Mexico. From Coventry Cathedral to Saint Margaret’s tiny stone chapel at the heart of Edinburgh Castle, from C.S. Lewis’s Oxford to T.S. Eliot’s Little Gidding, from the pastoral Wales of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s poetry to the English market town of Olney where John Newton penned “Amazing Grace”–all across the United Kingdom were places where men and women had borne generous witnesses to the faith within them. What attracted us to a location was not so much it’s physical topography as its spiritual biography.

Reassuring his disciples in Jerusalem’s upper room, Jesus promised that the Holy Spirit would “bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you” (John 14:26). We traveled in the light of that promise, asking ourselves: “What is here, in this place specifically, that the Holy Spirit might bring to our remembrance? If we will but listen, what aspect of the will and love of God is evinced by this place and by the persons who lived and sought God here?”

In our experience, the places in this book have been far more than sites of historical interest. They have, in different ways, been settings where that sort of holy listening, that kind of Spirit-led remembering, has happened to us. We found ourselves repeatedly recalling T.S.Eliot’s verse from the “Little Gidding” (not least at Little Gidding itself):

You are not here to verify….Instruct yourself, or inform curiousity…..

Or carry report. You are here to kneel……Where prayer has been valid.

We set out to visit these sites from St. Andrew, Scotland. We chose this town that feels like a village as our base for several reasons. Though unaffiliated with its medieval university we found that St. Andrews provided us with a priceless library collection on British Christianity, a girls’ school for our two daughters, and, not least, a home beside the North Sea. To the amazement of our neighbors, we even relished Scotland’s rain, which fell like a blessing on parched New Mexicans.

A pattern emerged during what became two years residence in Scotland, and during subsequent, shorter returns: After a period of preparation, having distilled all we could from the university’s library, we left St. Andrews, often from the nearest train station at the village of Leuchars, our trips timed as much as possible to good weather, thin crowds, and favorable tides.

….

Kneeling in these places “where prayer had been valid” has deepened the way we pray everywhere. We have come to see, with Elizabeth Barrett Browning, that “Earth’s crammed with heaven, and every common bush afire with God.” As Gerard Manley Hopkins perceived, “The world is charged with the grandeur of God.”

Of those places we chose to chronicle–settings illustrative of Britain’s vast spiritual landscape–many seemed to illumine certain facets of faith in particular. Scotland’s Whithorn, for example, where Saint Nina carried the gospel to unruly Picts, revealed the burden of witness and a call for Christians to speak despite unfavorable circumstances. Canterbury Cathedral, with its East Chapel’s focus on contemporary Christian martyrdom, put into relief the cost of discipleship from Thomas Becket down to the current day. Where better to wrestle with difficulties of forgiveness in our own lives than in the bombed-out ruin of old Coventry Cathedral and amid Coventry’s new, postwar Cathedral’s dedication to reconciliation?

We hesitate to call these destinations “sacred sites,” as though some settings (and by implication not others) offer domains of the holy. Perhaps, as Thomas More suggested, “there are places where God seems to want to be worshipped”; indeed, rocky outcrops of beauty like Lindisfarne and Iona can direct attention toward heaven just as observatories turn eyes to the sky. But at times pilgrims give credit to extra-ordinary place for experiences wrought more by dedication or ordinary time. After she heard visitors refer to Iona as a “thin place” where “there’s very little between Iona and the Lord,” Evelyn Underhill remarked, “I am far from denying that from our human point of view, some places are a great deal thinner than others: but to the eyes of worship, the whole of the visible world, even its most unlikely patches, is rather thin.”

This is one reason we include places off well-worn pilgrim tracks. As the poet William Cowper, coauthor with John Newton of Olney Hymns, wrote from England’s market town Olney:

Jesus, where’er Thy people meet,

There they behold thy mercy-seat;

Where’er they seek thee thou art found.

And ev’ry Place is hallow’d ground.

Our journey has yielded a wide view of the church in the world and a clearer perspective of our own calling. We discovered that we had not so much taken the journey as allowed it to take us—and strengthen and challenge us, and send us at times by the unforeseen routes. As George Macdonald once said of stories, true journeys somehow don’t seem to end. “The path of life is not only in eternity but towards eternity,” notes Grace Adolphsen Brame, “and the journey is not finished.”

For those who would visit these sites, either alone or in groups, we provide practical travel information in the Travel Notes. “The idea of pilgrimage is one that we badly need to recover today,” urges British writer Ian Bradley. Down through the centuries, the hope of drawing closer to God frequently provided the primary motivation for a journey. Particularly for visitors to Britain descended from Celtic, Catholic, and Reformed traditions, pilgrimage remains a way of travel that can orient lives of faith.

CHAPTER 1

WHITHORN AND SAINT NINIAN “The cradle of Scottish Christianity”

The journey began here for us, along the southwest coast of Scotland on the Galloway peninusla. If you can, seek out Ninian’s sea cave in the quiet of the day. —David

I walk to the cave in early morning, down an archway of sycamore, ash and oak, along an insistent stream and through a final cleft that frames the approaching sea. A right turn across a beach of smooth stones leads me up to the mouth of Saint Ninian’s cave.

The shallow recess sits a few yards above sea level, a damp, narrow crevice in Silurian slate, twenty feet high and equally deep, cloistered from any gale that might better this southwestern tip of Scotland.

Sixteen centuries ago, tradition tells us, NINIAN (c. 360-c. 432) walked here for silence and prayer, briefly withdrawing from his monastic community three miles away at Whithorn. Before arriving at this coast cell myself, I had imaginaed the Celtic saint huddled within the crevice’s damp shadows like Saint Cuthbert in his Farne Island hut, purposely having dimmed daylight lest the sun’s dazzle distract him.

But now I envision NINIAN on fine early mornings outside his cave on a tier of stones, sea-watching, gull-glancing, and letting God speak in the rinsed morning. Inside the cave I try to discern the rumored crosses etched into the slate. As my eyes grow sharper, I can see them slowly emerge from the darkness, faith as Ninian’s story itself.

What little we know about NINIAN comes from a handful of sources, chiefly a shore, captivating biography written in the 12th century by the Cistercian monk Aelred of Rievaulx and a free words by the chronicler Bede in the 8th century.

A hundred years before Columba arrived at Iona, NINIAN founded in 397 the first monastic settlement in what is now Scotland. Built from local shales and slates and lime-plastered white to glisten like a lighthouse in the sun, the monastery took on the name Candida Casa-the Latin becoming Whithorn (White House) in its Anglo-Saxon rendering.

British-born and Roman-educated, NINIAN preached and told the Christian story to the southern Picts, aboriginal inhabitants of Scotland. His father had ruled as a king of the Celtic tribe of the Britons, but the son turned his back on royalty. Like Saint Francis sloughing off his wealth, NINIAN exchanged entitlements for another currency. Not only compassion and zeal but also a certain breadth characterized his life; NINIAN excluded no creature from God’s grace, gathering even cattle and sheep together at night for a blessing. Biographers shower praise on him:devout, sagacious, bold, and, not least, attentive. An awareness of God graced NINIAN like an astronomer’s eye fixed to the sky. “It is characteristic of the saints,” observed Lucy Menzies, “that they tend gradually, little by little, to be transformed by that which they seek.”

The word first colors each reference to Ninian and Whithorn: the first stone church, the first monastic settlement, the first missionary in Scotland to tell others the gospel story. History leaved unanswered the question of who first told Ninian himself.

At the end of rolling countryside dipping down to the sea, Whithorn lies near both England and Ireland. From this coastal foothold, away from the crossroads of wars, Ninian witnessed boldly throughout Galloway’s peninsula. Celtic monks “alternated between periods of intense activity running their busy monastic familia and weeks or months of solitary withdrawal,” writes Ian Bradley in Colonies of Heaven.

The Celtic saint’s light pierced a dark inland landscape, humbling the painted Picts and unknotting tribal wars, as Aidan also would do later at Lindisfarne. My family name comes originally comes from this Scottish region; perhaps an unruly ancestor encountered Ninian himself. One author claims that “Ninian rescued Picts from barbarism,” turning them aside from idols, brutal ceremonies, and cycles of vengeance.

Such achievement can trigger scoffing today. Skeptics ask, “Isn’t barbarism in the beholder’s eye, and paganism merely a cultural preference?” Disputing the disease, they doubt a cure by the Cross. Moreover, they question Ninian’s very effectiveness: the Picts (so named by Roman soldiers for painting their skin) may eventually have washed off their conversion like one of their pigments. Which brings us face-to-face with Robin Lane Fox’s observation: The degree to which people ever become Christianized is a problem that recurs awkwardly in history “before foundering, as always, on the observable experience of our own lives.”

So perhaps Ninian retreated here to this cave in the way of failure and exhaustion. Like a later Scottish missionary, David Livingstone (whose lifetime tally of African converts numbered two), Ninian took solace in the scriptural charge to disciples that skims over “be effective” to fasten on the mandate “be faithful”.

Three sites in particular remain linked to Ninian: this damp, tapering cave of retreat; the monastic ruins of Candida Casa at Whithorn, three miles to the north; and lastly, down the coast, the Isle of Whithorn, where pilgrims once disembarked and knelt before walking inland to Candida Casa. These three equidistant landmarks–“a trio of localities which in historic importance and in sanctity are unsurpassed in the kingdom”–introduced some visitors to the Trinity and offered down the centuries a destination of solitude, witness, and prayer.

The Isle of Whithorn, a slender finger of turf and stone, juts into the Solway Firth a few miles down this indented coastline. Ninian’s legacy of healing miracles and posthumous relics attracted a steady train of medieval pilgrims, and after crossing the Irish Sea, they exchanged rolling ships for the isle’s steadying hummocks. A thirteenth-centre chapel, built atop an even older one, still deflects the wind and smooths the gait of anxious visitors.

A portion of the isle, joined now by causeway to the mainland, hums with the sound of harbor boats. But much of its ground retains an isolated charm, grooved with sheep trails running past rocky outcrops covered with lichen. At low tide, we white stones gleam as if freshly painted, hinting that those have provided the building blocks for Ninian’s settlement, stones so dazzling they disdained further lime-washed shine. Like the tenacious coastal settings of Iona and Lindisfarne, Candida Casa served as a whitewashed monument, a lighthouse designed not to warn but to attract, signaling that here are shoals on which one would wish to run aground.

In nearby Whithorn, now a town of twelve hundred people, a mound barely higher than the surrounding countryside entombs the probable site of Ninian’s ancient monetary. Above ground, the grassy rise hosts two churches–one new, the other ancient and roofless–along with wind effaced tombstones and fenced archeological digs. The Whithorn Trust’s highly regarded excavation work has burrowed through sixteen hundred years of history with Christian, Northumbrian, and Scandinavian layers of influence.

A controversy continues to swirl about the place. Does the mount with its persuasive ruins and artifacts indeed reveal the site of Candida Casa, or could Ninian’s monastery actually lie buried on the Isle of Whithorn? Ancient descriptions and current historians take issue with one another, trying to pinpoint the original locale of the “craddle of Scottish Christianity”. The dispute mirrors the Holy Land’s conflicts over terrain–whether Christ’s temporary tomb could be traced to Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulcher, despite the appeal of the tranquil, more evocative Garden Tomb.

Was the actual site here or only near here? Whithorn’s feuds point out the limits of identifying precise ground as sacred space, as though we could pin down holiness in the crosshairs of archaeology.

Ninian’s monks at Candida Casa lived in individual cells while sharing at the same time a corporate life. “His form of settlement was unlike anything that had been seen in Britain before,” explains Shirley Toulson in Celtic Journeys, “yet it was to become the model through the Dark Ages.”

The monks prayed and taught, studied and copied the Gospels and Psalms. Graced by “humility, compassion, and devotion,” the community drew students from Ireland and England. On this promontory “the seeds of Celtic Christianity took root and grew to flavor not only Britain but the whole of western Europe.”

Peering into the ruins, contemporary visitors can imagine monks bend assiduously in prayer, like later saints who “did not try to escape from the world” but “tried rather to transform it.” At other fields across Britain, crowds stand musing, anguished by battles that sowed the land with tombstones. But Whithorn’s grassy mound elicited a quieter sacrifice. In this field people gave lives rather than taking them. Pilgrims today can still unearth their shards of dedication.

I slept comfortably last night at a bed-and-breatkfast named after Saint Ninian. The owners are kind-eyed, humorous, and accommodating. As we stood in their kitchen after breakfast, they showed me honey gathered from their bees, one jar of heather honey, the other drawn from sycamore, hawthorn, and bluebonnet.

In addition to running the bed and breakfast, the husband and wife serve as lay Missionaries of Charity, the first two such associates of Mother Teresa’s order in all of Scotland. They have vowed poverty, obedience, conjugal chastity, and wholehearted and free service to the poorest of the poor. They earmark profits from the bed and breakfast for deprived families, convey medicines to the sick in Rumania, and take children in Whithorn on outings. Their compassion, quiet and deep, mingles with a certain gravity about God lightness about themselves.

They mention a friend of theirs, a priest, who once observed that “we can lose a lifetime practice of prayer in two days.” Why, we ask ourselves, should a devotional life so quickly atrophy? Why should God seem to slip out of sight? The answer, we agree, glints in our question: growing slack, we break our span of attention. Inattentive to our daily bread, we try to arrange for a weekly supply.

The medieval monk Aelred of Rievaulz, after extolling Saint Ninian’s love of humility, once groused nostalgically from his window on the twelfth century: “When I consider the devout walk and conversation of this man, I am ashamed of our negligence; I am ashamed of the sloth of this miserable age. ” Lest I too inclined to view Ninian’s characteristics as quaint relics, I see them reflected in faces across the kitchen.

The bed and breakfast sheltered only two other guests last night, a couple from Glasgow, she a tall attractive woman in her late forties, and he a red-bearded sculptor with wild, unkempt hair. A raconteur with a deep voice, he put his heavy boots on the living room table after dinner, told work-related stories with gruff irreverence, then asked what brought me to Britain.

I told him that Deborah and I intended to visit such sites as Lindisfarne and Iona, and Canterbury and Coventry Cathedrals. I spoke of places linked to Julian of Norwich, George Fox, and Evenlyn Underhill and mentioned qualities–a mysticism check by accountability, an evangelism infused with compassion–that drew me to them. As I concluded, I watched the sculptor’s piercing eyes and felt that he little understood my interest. This wooly-haired druid would have seemed most at home at Stonehenge than Canterbury Cathedral.

To my surprise, however, he began to speak about a trip he made made to Iona years before. “We took a wee boat down to the jetty,” he recalled, looking away. “People were all a-flutter, chattering, feet moving fast, and then partway across the Sound, you can see the change. They’re walking differently; they’re being different. I don’t know why. But it happened to us. People come looking for something.”

The sculptor turned his attention back to Nina and Whithorn as he rose to go to bed. “Tomorrow morning go early to Ninian’s cave. Go before anyone else gets there.”

And so I have, walking in the quiet to this place of retreat where people have returned to remember. On the night before his death, in one of his last utterances to his disciples, Jesus promised that the Holy Spirit will “bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you” (John 14:26, RSV). At times faith seem to have less to do with revelation than recollection. But where in our lives do we set out to remember? An old guidebook to Scotland described Iona as “the calling place” of pilgrims. With that double meaning–not only a place to call upon but a place to heed a call–these settings of retreat can orient us toward God and provide direction upon our return.

Far down the beach I glimpsed two people emerging from the archway of trees. They appear in no hurry to reach the cave, and, sitting down on the stones to look out one the Solway Firth, they give me a few more minutes of solitude.

Here near the cave bracketed by slate cliffs, I see Nina most clearly. He returned to drink in this restorative silence, no doubt arriving on wobbly legs and weariness in some years. In the sweet loneliness of the sea cave, Ninian’s boldness, elsewhere ground away, could be salted beside the waves.

I have taken my place at the end of a sixteen-hundred-year line of visitors to this place. Why have I come? To touch these incised crosses. “To kneel where prayer has been valid”? To gather my own bearings on a journey toward, win Thomas a Kempis’s words, “the country of everlasting clarity”?

As I leave the cave I walk over the cobbled beach, selecting along the way a handful of granite stones as gifts. Innumerable, smooth, and glistening, they seem beautiful as pearls. I spend more time considering the choices than I would before a display case.

I intend to bypass the two visitors seated on the stones, leaving them in their silence, but from a hundred yards away I hear my name called out in greeting and recognize the other guests from the bed and breakfast. Walking toward them, I marvel again that Ninian’s cross-lined cave should appear to the wooly-haired sculptor. But he asks gruffly how I found the cave and tells of other times he has visited. The sculptor appears glad that I took his advice to come early; having seen me at the cave, the couple purposely delayed their approach in order to give me more time.

We say our farewells; then as I start to leave, he reaches up from his sitting position to offer me a tin, rectangular piece of slate on which he has been scratching away with a stone as we talked.

“This is a gift for you, David,” he said, looking at me in the eyes. I glance down and see that on the slate’s smooth surface, the man whom I had pegged as a rough-hewn druid has etched with care a Celtic cross.